— By Lena from Malawi

It was a sunny Wednesday in mid-February. Together my colleagues from the CONGOMA, Lilongwe office, I set off to appreciate what impact NGOs are making in the communities. Ten kilometers from the Mchinji District north of the Boma, we were greeted by a sign post, saying “Welcome to Home of Hope”. I wasn’t sure whether this was the place we were looking for, so my colleagues decided to ask some young girls coming out of the gate. They confirmed it was the right place and we were eager to get in.

When we entered through the gates which we thought was the main gate, we saw the school buildings and pupils lingering about, only to realize it was around 10:30 in the morning and thus break time. The first observation I made was the presence of pupils and children of all ages, meaning this place did not discriminate; they took everyone in regardless of where they came from and how they got there.

As we approached the classrooms to ask where we could meet the authorities at the place, we were welcomed by a cheerful albino lady who directed us to the administration building. While Malawi as a country has a record of discriminating against and abuse of the disabled, people with albinism and orphans, just to mention a few, we noted how all these people had been embraced by the school. They looked free and happy.

We proceeded to the administration building, passing by several other buildings, including hostels, houses, a church, an auditorium, a maize mill and a garden. As we approached the building, we were welcomed by a slender, light skinned lady who ushered us into the Executive Director’s office. After introducing ourselves, we explained the purpose of our visit and the director sent us to Rev. Dr. Chipeta, who is the overseer of the place. We found him at the Guest House, where he was waiting for representatives of the Ministry of Education. He then took us to the office and told us about the founding and the history of HOME OF HOPE:

“I was born in 1929 in the northern part of Malawi. I lost my parents at the age of 15, so I was raised by my sister. Growing up in a home inhabited by children only was by no means easy as everything, from food to care, was handled by my sister who was as much a child as I was. In order to sustain us, my sister had to get married. Traditionally, a brother is not supposed to join a sister at her new husband’s house. This meant I had to be taken care of by an uncle.”

“Because I did not have the money to pay for school fees, I had to quit school in 1950. I could not pursue my studies as I had nowhere else to find the money. It broke my heart to drop out of school, yet the circumstances were beyond everyone’s control, so I accepted the situation, hoping for the best. In 1954, I moved to Mchinji, where I worked as a clerk at the Fort Manning Missionary. The godly environment at the missionary exposed me to several men of God who were an inspiration. Within due time, one Missionary guided me to Christ and I became a fully-fledged Christian by 1956. It was from this instant that I felt God’s calling to serve in His House and in 1957 I went to attend the Theological College in order to become a pastor in the Church of Central African Presbyterian (CCAP), Nkhoma Synod.”

“As soon as I had finished my studies, I was ordained to serve as a pastor in Zimbabwe for 15 Years. When doors open, blessings start to overflow; I had come form being an orphan and now I was a pastor. In 1978 I was sent to the University of Pietermaritzburg in South Africa, where I was awarded a diploma in theology for being a talented student.”

“Being an orphan myself I realized how many orphans lack the opportunities I had. After getting married in 1955, I lost two of my children in 1991 and 1992 respectively. Together they left behind ten orphaned children. This was the starting point for my vision for Home of Hope. I decided to retire as a Reverend and came back to Malawi to take care of my orphaned grandchildren. I had no money and the situation was helpless, but I managed to take on another 10 orphaned children, having a total of 20 orphans that my wife and I started taking care of.”

“I had no money but I had faith in God, and I was inspired by a strong vision that God was calling me to build an orphanage. Knowing the Ministry of Gender and Social Welfare’s requirements to set up an orphanage, I courageously decided on meeting them to share my vision. Not pursuing this vision was not an option. I shared the vision with Reverend Dr. Hara and Reverend Chiyenda and from that moment we started forming a board of trustees and applied for approval of an orphanage from the Ministry of Gender and Social Welfare.”

“Going by the motto ‘God is the Father of the Fatherless and he will sustain the orphanage’. When they rejected my application, I gave the Ministry my own testimony, including the reason I wanted to start an orphanage. By the grace of God, although I didn’t have the money, the project was approved. In 1996 we received 100 Malawian Kwacha as a start-up fund and since then, God has provided us and is still providing us.”

“Children need a lot of care, hence in the early stages of setting up the orphanage, I had my own children come to volunteer. I then employed my first treasurer, who used to be a managing partner at Graham Carr, called Loudon. He asked me whether I knew the story of Jesus. The story says that if a man wants to build a tower, he must sit down, estimate the costs and check if he has enough money to complete it (Luke 14:28). I told him I agreed, but continued to tell him that God would provide. Soon after, a friend of ours donated 38,000 Malawian Kwacha. This donation became the first money that we used to build the nursery for the orphans. At the moment, Home of Hope has many friends, who all have been very helpful. We have 700 children, a nursery, a primary and secondary school, while we are building a Technical College. We have our own health clinic with a clinical officer and a nurse appointed by the Ministry of Health.”

“Home Of Hope has made many friends in Malawi and beyond. With our work we have supported many children who are now self-reliant. For example, some are doctors, others work in field of finance or communication. Although we have done much, we are still in need of 8 staff residences. I, Reverand Chipeta, due to my commendable work, have been awarded the 2000 Bob Pierce Award by the founder of World Vision, a Paul Hals fellowship, the Our People Our Pride Award, a Rotary Club fellowship and an award for 50 years as a pastor of the Church of Central African Presbyterian (CCAP). Conclusion: always help the needy as you never know where they will be tomorrow.”

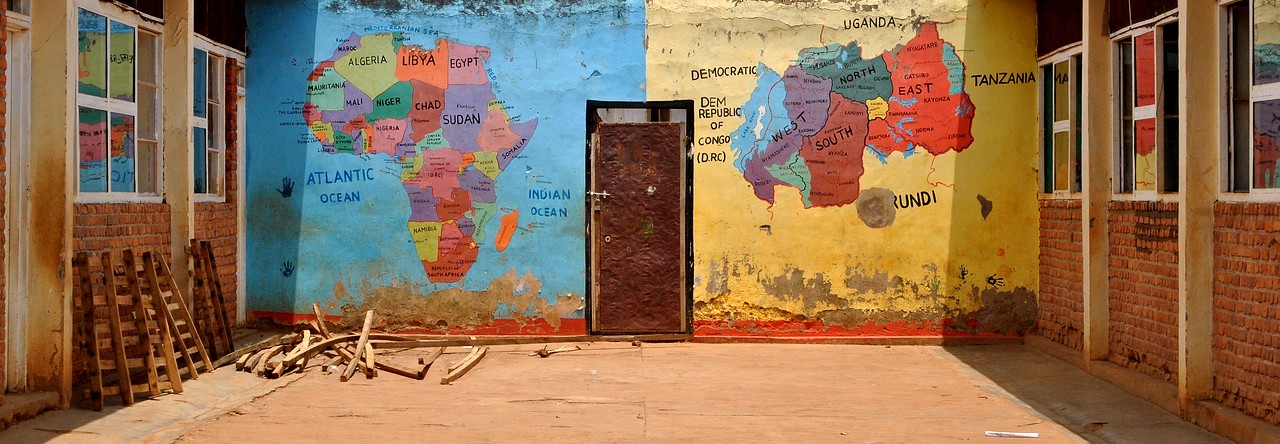

After this powerful plea, the Reverend took us around the area. We were shown a perfect home that every orphaned child would ask for, with a perfect view of the mountain. We walked by the houses, the hostels, the classrooms, a guest house, the technical college, the library and the path to the main gate we were supposed to enter from. First, we were shown the nursery, which was the first building built and named after the donor that supported its construction. As we entered, we met happy children varying between the ages of two weeks to three years old. They were all cheering and calling the Reverend ‘Agogo!!’ which means ‘grandfather’. We saw a two-week old baby and a three-month old baby, who both arrived a day after their birth. As their nannies came to greet us, the Reverend introduced them to us and told us of the tremendous work they do, taking care of the children. As we moved on, we saw different buildings named after their sponsors. We got to the girls’ hostel and we went to the Technical College, which is still under construction. As we walked on to the small gate facing the hill, there was a garden where different crops were grown. When we continued to see the view, one gentleman came to the Reverend and told him about the arrival of the visitors he had been waiting for.

After the tour, Reverend Chipeta took us to the Guest House where we were offered refreshments. Immediately after the refreshments, the visitors from the Ministry of Education, who had also done a tour while awaiting the reverend, arrived to the Guest House. We exchanged greetings and when I looked at my watch, I realized it had been over 2 hours since we arrived.

As we left the Rev. Dr. Chipeta, who called himself a 88-year old young boy, we were all left inspired. If you are inspired as well after reading and you would like to support the Home of Hope, you can contact Rev. Chipeta via email (mchinjihoh@gmail.com) or visit their website (www.homeofhopemalawi.org).