— By Nobantu from South Africa

— By Nobantu from South Africa

From November 2nd to November 5th 2017, 70 participants and alumni from the Aileen Getty School of Citizen Journalism travelled to Jordan together to partake in a weekend of learning, dialogue, and fun. This is Nobantu’s experience:

There was a wise king who lived a millennia ago and was revered the world over. Among his treasured written works was a particularly poignant reflection on life, in which he said that there is a time and a season for everything under the sun. A time to be born and a time to die. A time to plant and a time to reap a harvest.

I will be the first to admit that I have been fairly spoiled as far as my time for experiencing the miraculous is concerned. I was born in political exile to a family of anti-apartheid activists, thereby inheriting a very rich and unique legacy. A miracle of its own. I grew up in a democratising South Africa, making strides to forgive and reconcile, as opposed to degenerating into the brutal civil war the world anticipated. A total miracle. I had the great fortune of going to brilliant schools and accessing opportunities which my toasted caramel skin would never have accessed pre-1994. Miraculous. Nelson Mandela was my President…epic!

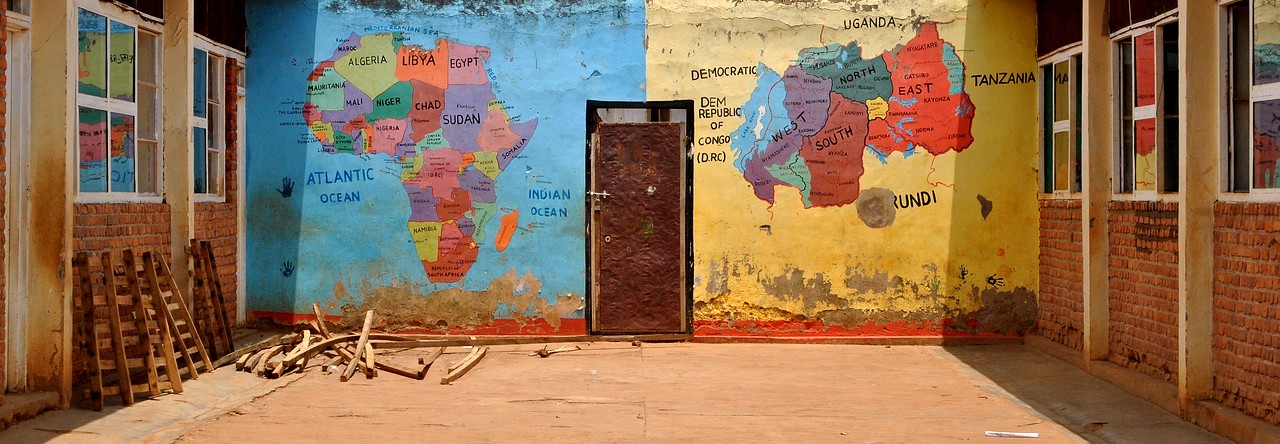

As it would be, November 2- 5 was my time to experience an unforgettable miracle which stretched beyond my republic into the arms of a borderless, loving family known as YaLa Young Leaders. Under a banner of progressive thinking, what the world would most likely deem an “unlikely set of fellows” converged into a well facilitated series of exchange and…well…fun! 70 bright young minds came from Israel, Palestine, Iraq, Kurdistan, Algeria, Morocco, Tunisia, Egypt, Sudan, South Africa, and Zimbabwe, to Amman, Jordan for Yala’s Alumni Citizen Journalism Conference. The program and set of lecturers were especially arranged to refine our skills in journalism, public speaking, writing and peace activism. More than anything, I wish we had an extra week, at the very least, to explore varying contentious issues related to peace building and peace activism, because it is a vast and delicate set of topics that cannot be rushed, whether approached from a Middle Eastern or African perspective.

Reflecting on my time in the Spring 2017 cohort, as well as in my time at this conference, I highly appreciate that YaLa has restructured, coloured, and animated a poorly cast image of a very special region. All I was exposed to before was the calculated assertions of academia and the impersonal generalizations of mainstream media. Now I have had the honour of being exposed to sets of narratives that few have done justice to. Having met my peers and counterparts, I see no difference between us. Whether South African or Middle Eastern, we have our set of introverts and extroverts. We are dancers, philosophers, mathematicians, business people, and the hilarious one or two who just shaved off 10 years from their biological age. *Wink* But ultimately, we are just people. People willing to care. People willing to do. People willing to navigate our way through landmines of trauma, religious sensitivities, and…well…you have to apply for the programme to find out the rest.

As fulfilling as it is to simply bask in the beauty of this miracle known as YaLa, and its network of astute young leaders, I cannot help but ask, “What are the odds?”

What are the odds that I would jet off from the southern-most tip of Africa to see young Israelis and Palestinians learning together, being vulnerable with each other…then bonding over Bamba? What are the odds that this unlikely collection of nationalities would be excitedly buzzing around a resort, simulating news rooms and generating content dissecting critical topics? What are the odds that from societies stubbornly set on continuing divisive tugs of war that there is a resilient, like-minded set of young people stirring a current to initiate change? What are the odds that most of us arrived not knowing a single soul but left a changed person? I expected to learn, but what are the odds that I would meet so many kindred spirits? What, indeed, are the odds?

Having grown up in the miracle of a democratising state has not, in any way, made me immune to recognising and cherishing a special miracle when I see one. More than anything, I see more clearly a time where my heart swells to replicate the miraculous. I see a time where a change-maker is no longer a lone wolf, howling into unforgiving winds, but part of a bold, eager pack – rabid to redefine what should be deemed acceptable. I see a time when inspiration and action are colliding to re-shape the world that we live in.

More than anything I see a season to exclaim: “Yalla…let’s go!”